Abstract: Delaware's CORE early intervention program serves 12-25 year olds with First Episode Psychosis or those at clinical high risk. The article describes study methods and measured changes in participants' social functioning.

"Changes in Social Functioning in Delaware CORE" (2019)

Adina Seidenfeld & Charles Webb

Young adults' ability to cope with new clinical information about their health relies on adequate social functioning for communicating needs and seeking social support. However, in the case of psychosis, social functioning or how one maintains relationships can be impaired before or during an episode.1 In fact, difficulties with social functioning may be both a risk factor for and consequence of psychotic development.2

Unfortunately, the evidence for effective promotion and recovery of social functioning in people who have psychosis is not consistently strong.3 Measurement of social functioning may vary depending on whether clinicians or clients are the reporter.4 There also is initial evidence that individuals who have had a first episode of psychosis (FEP), compared to those at clinical high risk (CHR) for an episode, may exhibit more recovery of social functioning after treatment.5 Another possibility is that perceived support may contribute to improved social functioning, as one study found family treatment involvement associated with improved social functioning.6 Together, inconsistencies of treatment impact on social functioning may be attributed to how social functioning is measured, stage of psychosis onset, and perceived support.

Present Study

Delaware Community Outreach, Referral, and Early Intervention Program (CORE) is an early intervention program for Delawareans ages 12 to 25 with FEP or CHR. CORE utilizes a coordinated specialty care model. A multidisciplinary team (comprised of a prescriber, occupational therapist, supported education and employment specialist, and clinician) works together with the client to address symptom management, social functioning, and educational and/or occupational functioning. The program is modeled after the Portland Identification and Early Referral (PIER) program developed by Dr. William McFarlane.7 CORE provides education about psychosis not only to the client, but also to family members. Clients and family members are invited to attend multifamily groups where they engage in collaborative problem solving and have opportunities to build a supportive social network. These activities are based on the theorized importance of social support for reducing stress and improving overall outcomes.7

The present sub-study of Delaware CORE examined program impact on social functioning, as reported by both clinicians and clients. It was expected that clinician and client report would differ, although the direction of that difference was unclear based on the literature. Researchers also hypothesized that risk status (i.e., enrollment as FEP or CHR) and clients' perception of social connectedness would change the effect of CORE on social function. Based on the results of one study, we expected that persons with FEP would show greater improvement over time. We also expected that participants with greater social support would benefit more from CORE than those endorsing less social support.

Study Methods and Results

Participants and their assigned clinicians rated participants' social functioning at enrollment, and at 6- and 12-months post-enrollment. Participants were categorized as either CHR or FEP according to the results from the Structured Interview of Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS).8 Clinicians rated participants using the MIRECC Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) social subscale, which ranges from 0 (no information available) to 70 (average functioning) to 100 (superior functioning). On the National Outcome Measures (NOMs),9 participants rated their agreement (from 0 [strongly disagree] to 4 [strongly agree]) with two statements: "I do well in social situations," and "In a crisis, I would have the support I need from family or friends." The latter item served as a proxy for perceived social support, and correlated positively with other NOMs items that measure social connectedness (e.g., belonging to a community).

At the time of this report, two or more assessments were collected on 44 (81%) clients who were enrolled for at least 1 year. Average age at enrollment was 17.7-years-old (range 14- 24-years-old), with a majority of the sample describing themselves as male (~64%), and non-Latino Caucasian (~55%). About 55% of the sample qualified as CHR. Most of the clients with FEP resided in New Castle County, the most populated, urban, and culturally diverse of the state's three counties.

At enrollment, participants did not differ by their enrollment status of CHR or FEP on clinician or participant ratings of social functioning. Moreover, there was no significant correlation among clinicians' social rating on the MIRECC and clients' ratings of social well-being or support in a crisis.

Analyses revealed that not all CORE participants improved their social functioning. Instead, treatment-related changes in social functioning depended on other factors and varied by reporter.

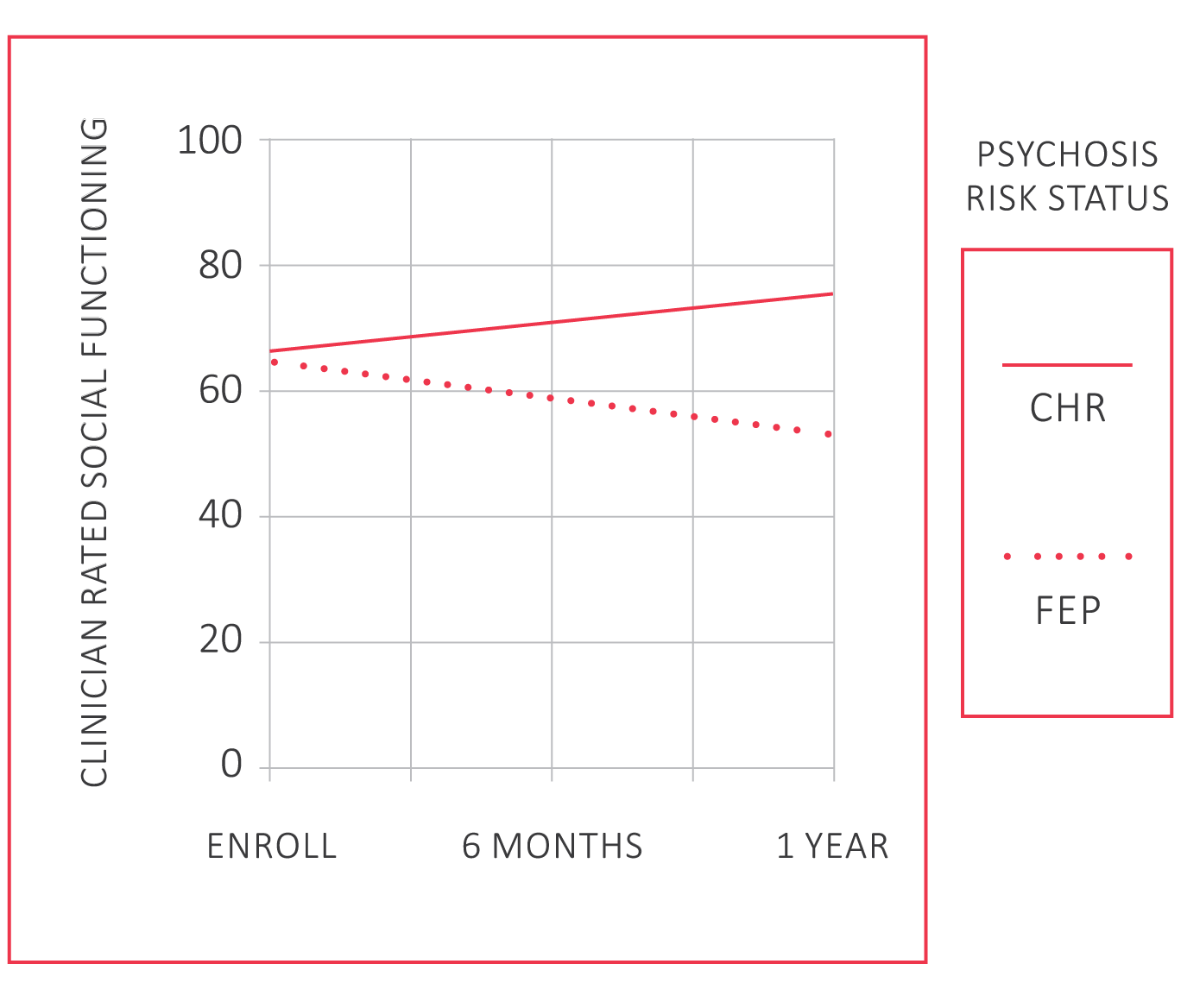

Per clinician report, FEP social functioning declined during treatment, whereas CHR improved after a year of treatment; see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Treatment Changes in Social Functioning by Enrollment Status

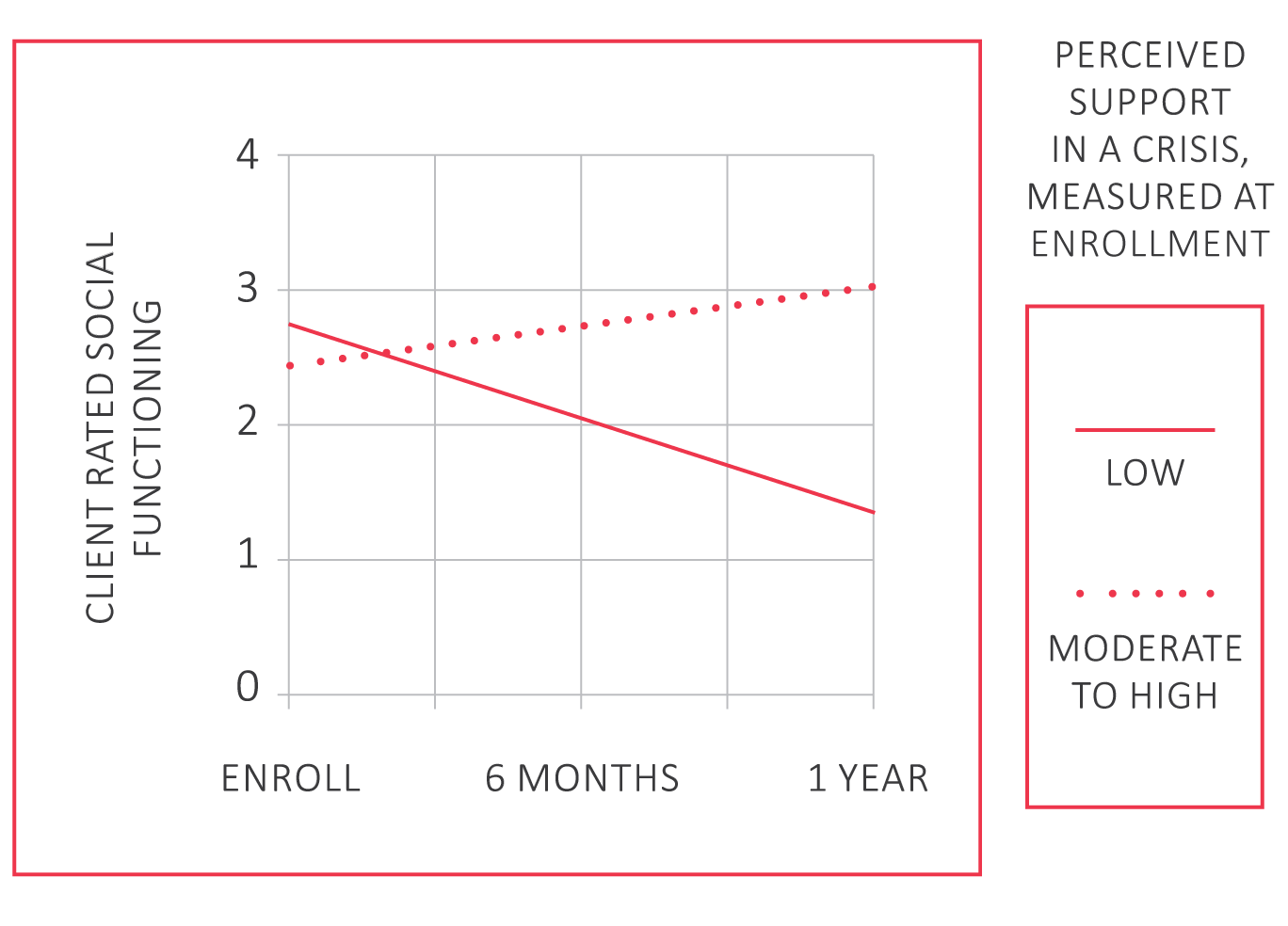

Figure 2 shows that clients endorsing higher levels of support in a crisis reported improvements in their social functioning; whereas, those endorsing lower levels declined.

Figure 2. Treatment Changes in Social Functioning By Perceived Support in a Crisis

Lessons Learned

The findings highlight the importance of rater perspective. Clients did not report similar social functioning to clinicians – rating themselves with lower levels of social impairment. Differences between reports may be the result of low awareness, lack of comfort in reporting, or an artifact of clinicians' classification of participants as CHR or FEP.

These results emphasize the importance of accessing services early, even before youth and young adults experience a first episode of psychosis. Those with CHR may respond better to treatment of social functioning. Other strategies may be needed to support the social skills of those with FEP.

Clients' perceived support in times of crisis affected changes in self-reported social functioning over time. Those who reported low levels of support reported a decline in social functioning; those who reported higher levels reported improvements. Social support may be an important condition of social recovery. Learning of a loved one's mental health condition can be hard on family members; however, it is important that they show strength and lend support to the affected youth or young adult. Family members may even want to seek their own support from friends, family, religious organizations, or other groups.

A few considerations about these results are worth noting. These results are preliminary, and may change as Delaware CORE collects more data. Analyses did not include a control group, so it is unclear how participants would have done compared to a non-treatment group. Additionally, it is unclear how these results may generalize to families not enrolled in Delaware CORE. Despite these limitations, results provide evidence for the importance of capturing and promoting social functioning in young people with early psychosis.

References

- Addington, J., Penn, D., Woods, S. W., Addington, D., & Perkins, D. O. (2008). Social functioning in individuals at Clinical High Risk for psychosis. Schizophrenia Research, 99(1-3), 119–124.

- Cornblatt, B. A., Carrion, R. E., Addington, J., Seidman, L., Walker, E. F., Cannon, T. D., … Lencz, T. (2012). Risk factors for psychosis: Impaired social and role functioning. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38(6), 1247–1257.

- Menezes, N. M., Malla, A. M., Norman, R. M., Archie, S., Roy, P., & Zipursky, R. B. (2009). A multi-site Canadian perspective: Examining the functional outcome from first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 120, 138–146.

- Bastiaansen, D., Koot, H. M., Ferdinand, R. F., & Verhulst, F. C. (2004). Quality of life in children with psychiatric disorders: Self-, parent, and clinician report. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(2), 221–230.

- McFarlane, W. R., Levin, B., Travis, L., Lucas, F. L., Lynch, S., Verdi, M., … Cornblatt, B. (2015). Clinical and functional outcomes after 2 years in the early detection and intervention for the prevention of psychosis multisite effectiveness trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 41(1), 30–43.

- Marino, L., Nossel, I., Choi, J.C., Nuechterlein, K., Wang, Y., Essock, S., … Dixon, L. (2015). The RAISE Connection Program for early psychosis: Secondary outcomes and mediators and moderators of improvement. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 203(5), 365–371.

- McFarlane, W. R. (2002). Multifamily groups in the treatment of severe psychiatric disorders. New York, NY: Guilford.

- Miller T. J., McGlashan, T. H., Rosen, J. L., Cadenhead, K., Ventura, J., McFarlane, W., … Woods S.W. (2003). Prodromal assessment with the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes and the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms: Predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 29(4), 703–715.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, US Department of Health & Human Services. (2010). National Outcome Measures. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/grants/gpra-measurement-tools

Suggested Citation

Seidenfeld, A., & Webb, C. (2019). Changes in Social Functioning in Delaware CORE. Focal Point: Youth, Young Adults, and Mental Health, 33, 20–22. Portland, OR: Research and Training Center for Pathways to Positive Futures, Portland State University.