Abstract: This article expands on the need for trauma-informed collaboration with youth and their critical participation in planning, reforming, and implementing successful organizational services aimed towards young adults.

"Trauma-Informed Method of Engagement (TIME) for Youth Advocacy" (2015)

Over recent years there has been growth in the number of provider organizations and agencies that require youth and young adults who are current or former recipients of services to participate in their own care planning and take an active role in systems reform efforts. In an attempt to better incorporate these young adults (YAs) in systems reform, many supportive adults (SAs) are directed to find young persons who have a "success story" and ask them to serve on a committee/board, or speak at some event. While this effort has given youth and young adults an opportunity to share their experiences, it has come with little awareness or guidance on how to prepare them. When youth share their stories they often talk about very traumatic life experiences, and this can lead to unintended negative consequences. Such consequences can cause severe effects such as re-traumatization, flashback episodes, overwhelming feelings of hopelessness, severe emotional responses, substance abuse relapse and/or mental health episodes, and even suicidal thoughts or ideation.

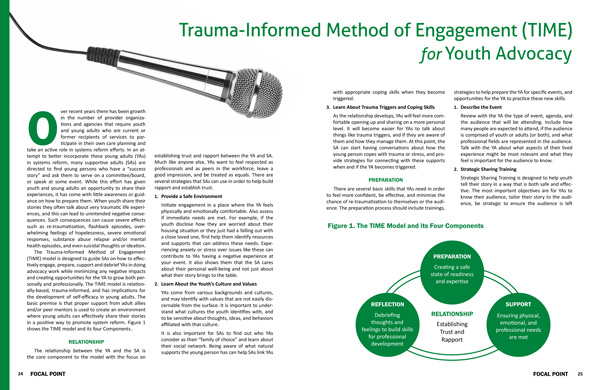

The Trauma-Informed Method of Engagement (TIME) model is designed to guide SAs on how to effectively engage, prepare, support and debrief YAs in doing advocacy work while minimizing any negative impacts and creating opportunities for the YA to grow both personally and professionally. The TIME model is relationally-based, trauma-informed, and has implications for the development of self-efficacy in young adults. The basic premise is that proper support from adult allies and/or peer mentors is used to create an environment where young adults can effectively share their stories in a positive way to promote system reform. Figure 1 shows the TIME model and its four Components.

Figure 1. The TIME Model and its Four Components

Relationship

The relationship between the YA and the SA is the core component to the model with the focus on establishing trust and rapport between the YA and SA. Much like anyone else, YAs want to feel respected as professionals and as peers in the workforce, leave a good impression, and be treated as equals. There are several strategies that SAs can use in order to help build rapport and establish trust.

- Provide a Safe Environment. Initiate engagement in a place where the YA feels physically and emotionally comfortable. Also assess if immediate needs are met. For example, if the youth disclose how they are worried about their housing situation or they just had a falling out with a close loved one, first help them identify resources and supports that can address these needs. Experiencing anxiety or stress over issues like these can contribute to YAs having a negative experience at your event. It also shows them that the SA cares about their personal well-being and not just about what their story brings to the table.

- Learn About the Youth's Culture and Values. YAs come from various backgrounds and cultures, and may identify with values that are not easily discernable from the surface. It is important to understand what cultures the youth identifies with, and to be sensitive about thoughts, ideas, and behaviors affiliated with that culture. It is also important for SAs to find out who YAs consider as their "family of choice" and learn about their social network. Being aware of what natural supports the young person has can help SAs link YAs with appropriate coping skills when they become triggered.

- Learn About Trauma Triggers and Coping Skills. As the relationship develops, YAs will feel more comfortable opening up and sharing on a more personal level. It will become easier for YAs to talk about things like trauma triggers, and if they are aware of them and how they manage them. At this point, the SA can start having conversations about how the young person copes with trauma or stress, and provide strategies for connecting with these supports when and if the YA becomes triggered.

Preparation

There are several basic skills that YAs need in order to feel more confident, be effective, and minimize the chance of re-traumatization to themselves or the audience. The preparation process should include trainings, strategies to help prepare the YA for specific events, and opportunities for the YA to practice these new skills.

- Describe the Event. Review with the YA the type of event, agenda, and the audience that will be attending. Include how many people are expected to attend, if the audience is comprised of youth or adults (or both), and what professional fields are represented in the audience. Talk with the YA about what aspects of their lived experience might be most relevant and what they feel is important for the audience to know.

- Strategic Sharing Training. Strategic Sharing Training is designed to help youth tell their story in a way that is both safe and effective. The most important objectives are for YAs to know their audience, tailor their story to the audience, be strategic to ensure the audience is left with the primary message, and manage appropriate responses to questions.1 2 3

- Help Develop Message and Method of Delivery. Work with YAs to choose a method of delivery they will be most comfortable with (speaking, using PowerPoint slides, other visual aids, etc.) Once a method is chosen, help YAs think through and research what information is available on the topic. Although the YAs' stories should illustrate problems, they also need to present solutions to what they experienced, including what resources and services they found helpful, as well as what evidence and best practices are available. The SA may want to sit with YAs as they talk through their message and method of delivery. It may be beneficial to have the YAs practice with a variety of people, potentially their peers, other SAs and/or a mental health professional.

- Develop a Support/Wellness Plan. Create a "support/wellness plan" outlining action steps in case a YA is triggered during participation. This plan will serve as a guide on how to access positive coping mechanisms and avoid negative ones.

- Review Logistics. The SA or asking organization should talk through the logistical details for participating in the event. Not having appropriate preparation for support for logistics can be traumatizing and leave young people feeling alone or abandoned. This can result in stress which may lead to relapse into substance abuse or mental health episodes. National Resource Center for Youth Development3 has a comprehensive youth travel guide that the SA should use when developing a travel plan with YAs.

Support

Support, the third component of the model, seeks to ensure that physical, emotional and professional needs are met during the event. While support of YAs is necessary throughout the entire process, this component is focused on the event itself. Key strategies for supporting the youth during the event are as follows.

- Set Up for Success. Ideally, the SA will be onsite to meet the YAs if they did not travel together. The SA should ensure that the agreed upon details are in place. The SA should also provide encouragement during the event if present, or connect the YAs with other potential allies to provide support through the event. Check in and arrive at the room early to get a feel for the event. Have the YAs stand in the spot from which they will be delivering the speech, and if time allows, have the YAs practice at least the major points of their message.

- Visible Support. If the SA is neither moderating the panel nor onstage with the YAs, the SA should sit in a position where there is good visual contact. The SA should provide ongoing encouragement and reassurance throughout the message through non-verbal cues such as nodding, smiling, eye contact, etc. The YAs and SA should also implement agreed upon non-verbal cues to communicate "slow-down," "speed up," "speak louder," "five minutes left," etc. If a YA does get triggered during the event, implement the Support/Wellness Plan that was developed beforehand. This may include the SA fielding questions for the YAs, offering an 'additional thought' to allow them a moment to manage their emotions, or delivering a previously agreed upon message on behalf of the YAs.

- Post Presentation Support. After the YAs finish the event, audience members are likely to approach them to talk further about their message. During this time, it can be helpful for the SA to be near the YAs to help assess for emotional vulnerability, field questions, and help facilitate networking opportunities. Immediately after the audience members are addressed, a short check-in should occur with two primary components: emotional support and professional development. It is important to focus separately on the emotional processing and professional processing by first validating the YA's feelings and experience, and then asking about the content and delivery of the event.

Reflection

The last component is Reflection. During this component, the SA reflects on strengths and needs of each youth during the event. The purpose is to help the YA further improve professional skill development, identify safety issues like trauma triggers, and provide support in helping the YA access appropriate coping mechanisms and/or resources to address triggers. The effectiveness of the Reflection component relates back to the level of trust and relationship between the YA and SA, and other supports that the YA has or needs. Key strategies during the Reflection component include the following:

- Debrief the Event Thoroughly. While some of this may have happened in the immediate debrief of the event, for the YA's professional and personal development it is important to revisit what was discussed based on the goals of the YA. The YA might have a different opinion once given time to process everything that occurred during the event. The SA should provide constructive feedback and encouragement, discuss strengths and areas for growth, discuss personal insights gained, and discuss additional goals, including resources and trainings for future professional development.

- Personal and Professional Development Opportunities. Encourage YAs to:

- Access peer networking and support

- Find and stay connected to formal/informal peer support groups

- Obtain additional advocacy trainings

- Talk to a therapist, mentor and/or adult support partners about new insights

- Engage in activities that help with cultural healing and growth

- Explore awareness of new triggers and coping strategies

- Refine their support/wellness plan

- Identify and participate in other advocacy events

- Take on a leadership role and participate in leadership training

- Develop future goals

- Family Programs and Foster Care Alumni of America. (n.d.). Strategic sharing. Seattle, WA: Author.

- Federation of Families for Children's Mental Health. (2012). Strategic sharing workbook: Youth voice in advocacy. Portland, OR: Research and Training Center for Pathways to Positive Futures.

- National Resource Center for Youth Development (NRCYD). (2011). Youth leadership toolkit. Tulsa, OK: National Resource Center for Youth Development. Retrieved from http://www.nrcyd.ou.edu/learning-center/publications/Youth%20Leadership%20Toolkit/All

Implications

Having youth voice present in organizations and at events is one of the critical components for changing the way systems improve their outcomes for children, youth, young adults, and families. However, because of potential unintended consequences that arise when youth are engaged in system reform efforts, it is critical for both SAs and YAs to be trauma-informed. The risk of being negatively impacted by sharing one's traumatic experiences can be greatly reduced when proper preparation and supports are put in place.

The TIME model provides a foundation for the development of policies and guidelines that can help to minimize the likelihood and potential negative impact of re-traumatization for YAs. Organizations that engage YAs should incorporate TIME model practices into their engagement activities to help ensure safer and more productive advocacy.

References

Suggested Citation

Cady, D., & Lulow, E. C. (2015). Trauma-Informed Method of Engagement (TIME) for Youth Advocacy. Focal Point: Youth, Young Adults, and Mental Health, 29, 24-27. Portland, OR: Research and Training Center for Pathways to Positive Futures, Portland State University.